Simply put, an interval is the distance between any 2 notes. Let’s take a quick example. For a guitar player, any note is just a fret being played. Similarly for a piano player, any pressed key is a note. Now if you were to play another note, there actually is a name for the distance between the 2 notes that were played. This name will be one of the different intervals that we shall study.

The reason why we need intervals can also be understood by the example shared above. For the distance between a C and D, a guitar player will probably say “2 frets ahead” while a piano player might say “the white key to its right”. Having a name for this interval will just keep things standard for all instrumentalists thereby making things easy.

In popular Western Music Theory, any interval has 2 main parts in its name which will be a quality and a number. Quality of the interval will be defined as major, minor, perfect, augmented, diminished while the numbers will be second, third, fourth etc. Put these 2 together and you will have the name of the interval. However, not every single one of these qualities will go with every number. So we have an interval called major second (major 2nd) but none called perfect second (perfect 2nd). Hope you guys have understood so far!

So how many intervals do we have and what are their names?

Let’s take a quick look at all the notes that we have as this will help understand the different intervals well. In total we have 12 notes which consist of 7 natural notes and 5 accidentals (sharps/ flats).

c c#/db d d#/eb e f f#/gb g g#/ab a a#/bb b C

To keep things simple, let’s start off with the ‘C’ note.

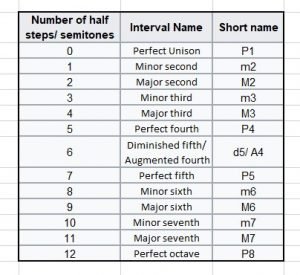

1) c c

If we were to play 2 ‘c’ notes together, this would be our first

interval. Here the distance between the 2 notes played is 0. Such an

interval is called a Unison or a Perfect Unison, represented by P1. Totally

understandable if you would have preferred perfect first instead of

perfect unison but that’s just how Music Theory goes ![]()

2) c c#/db

This interval would be called a Minor 2nd and is represented by m2. Simply put, a minor 2nd interval is a half-step or semitone away. For guitar players, this would mean one fret away.

Please note that just like a ‘c’ to ‘c#’ is a Minor 2nd interval, a ‘c#’ to a ‘d’ is also a Minor 2nd interval as we are simply referring to the distance between the 2 notes in question which is the same as a half step/ semitone away.

3) c d

This interval would be called a Major 2nd and is represented by M2. Simply put, a major 2nd interval is a whole-step or tone away. For guitar players, this would mean two frets away.

Again note here that from ‘c’ to ‘d’, the interval is a Major 2nd but from ‘c#’ to ‘d’, is a Minor 2nd. Hope there are no confusions there.

4) c d#/eb

This distance is 3 half steps or 3 semitones away and is called a Minor 3rd and is represented by m3.

5) c e

This distance is 4 half steps or 4 semitones away (or 2 whole steps) and is called a Major 3rd, represented by M3.

6) c f

This distance is 5 half steps or 5 semitones away and is called a Perfect 4th and is represented by P4.

7) c f#/gb

This distance is 6 half steps or 6 semitones away and is called an Augmented 4th (A4) or Diminished 5th (d5). Note that this interval is also called a Tritone as it is composed of exactly 3 full steps or 3 whole tones

8) c g

This distance is 7 half steps or 7 semitones away and is called a Perfect 5th and is represented by P5.

9) c g#/ab

This distance is 8 half steps or 8 semitones away and is called a Minor 6th and is represented by m6.

10) c a

This distance is 9 half steps or 9 semitones away and is called a Major 6th and is represented by M6.

11) c a#/bb

This distance is 10 half steps or 10 semitones away and is called a Minor 7th and is represented by m7.

12) c b

This distance is 11 half steps or 11 semitones away and is called a Major 7th and is represented by M7.

13) c C

This distance is 12 half steps or 12 semitones away and is called an Octave or a Perfect Octave and is represented by P8.

Here’s a table summarising the names for all of the intervals that we just learnt about.

A couple of points that I would like to add here for the satisfaction of hardcore music theory enthusiasts.

a) All intervals are ditonic (have two tones/notes). Kindly note that this is different from being diatonic (which refers to the concept of progressing through all the tones). An interval cannot be formed with a single note or more than two notes.

b) Intervals can also be classified as melodic or harmonic. A melodic interval would be when you play one note after the other (as in a melody) while a harmonic interval would be when you play 2 notes simultaneously (like a harmony). A power chord (like an A5 chord) would be an example of a harmonic interval

c) Intervals can be names either in minor-major-perfect intervals (like we just did), but also have similar names with just the augmented-diminished qualities. But we will ignore that to keep things simple. To give an example of what I’m trying to say, the perfect unison can be called a Diminished 2nd, Minor 2nd is the same Augmented unison etc. But why confuse yourself when we can keep things simple, right?

d) The above concept of one interval having multiple names is also seen in sharps and flats. An A# is the same note (has the same pitch) as Bb. But we do have different names depending on the context (will explain this in a different article). Such notes are called enharmonic notes (same pitch, different spelling) just like the intervals with 2 different names are called enharmonic intervals (same pitch, different spelling)

e) The smallest of the intervals that we just learnt about was the

semitone or half step. This is in line with the Western tuning of 12

equal semitones per octave. Actually we can also have intervals smaller

than a semitone which are called microtones, but who has the energy to learn more when these. Not me!!!! ![]()

How to master Intervals

So there you go! That’s the beginner guide to knowing about intervals. However, just knowing the names is obviously not enough. A good musician needs to completely internalise all intervals as they can be a huge arsenal while making music and improvisation. This is what I would recommend you to do now.

1. Take any note and try to understand the sound of all of its intervals. This may seem difficult but the best way to do this is to associate these intervals with some songs. For example, a perfect unison is the sound that you hear when you sing ‘happy’ in ‘happy birthday to you’. Get it? Try to associate all the intervals with songs that you know and remember.Try to fully associate one interval daily for the next 13 days

2. Memorise the position of each interval. For example, if I were to play any note on the 6th string of a guitar, the perfect 4th would be right below it on the 5th string. Similarly it’s major 3rd would be one string down and a fret to the left. A position internalised daily would be great for future improvisations

Believe me on this one! Intervals are definitely the least sexy amongst all other concepts in music theory. But they will always be the building blocks and will stay crucial when it comes making music and also appreciating it. Understanding these small relationships will make future understanding of larger patterns a lot easier while also helping to control the emotional effects they create for the listeners.

Practice slow and very soon, you will see your playing and understanding of music move to the next level. That is when you will be patting yourself on the back for having taken out the time to learn these.

- All the best!